Foreigners Continued to Have Control After Independence Because They Brainlyt

Democratic Control of Foreign Policy

"If there is to be war, it should be the people themselves that choose it with their eyes open."

I.

On November 23, 1912, there appeared in the London Times a remarkable article, from which the following is an extract: —

'Who then makes war? The answer is to be found in the Chancelleries of Europe, among the men who have too long played with human lives as pawns in a game of chess, who have become so enmeshed in formulæ and the jargon of diplomacy that they have ceased to be conscious of the poignant realities with which they trifle. And thus war will continue to be made, until the great masses who are the sport of professional schemers and dreamers say the word which shall bring, not eternal peace, for that is impossible, but a determination that war shall be fought only in a just and righteous and vital cause.'

Less than two years later the great war broke out; and at the first shock of it, it was regarded as just such a war of diplomats. Thus the Standard, a conservative organ, said on August 3, 1914: —

'We do not know what sort of children our grandchildren will be, but if they are at all like ourselves they will recall with astonishment how Europe went to war in 1914 without passion, or hatred, or malice—how between two and three hundred millions of people set out to slaughter one another in a fatalistic way merely because the diplomatists had arranged things so. … The Powers of Europe are at each others' throats in obedience to a barren diplomatic formula.'

Presently, under the stress of war, this truth became too intolerable to be credible. People cannot fight unless they believe that they are fighting for a great cause; and so, in fact, they always manage to believe it. None the less, these voices at the outset of the war were the true ones. It is a diplomats' war. None of the peoples wanted it, and none of them would have stood for it, if in some way they could have been jointly consulted in the light of full knowledge of the fact. But they were not consulted, either jointly or severally, no more in the countries called democratic than in the autocracies. If they had been, there would have been no war. Hence the movement for the democratic control of foreign policy.

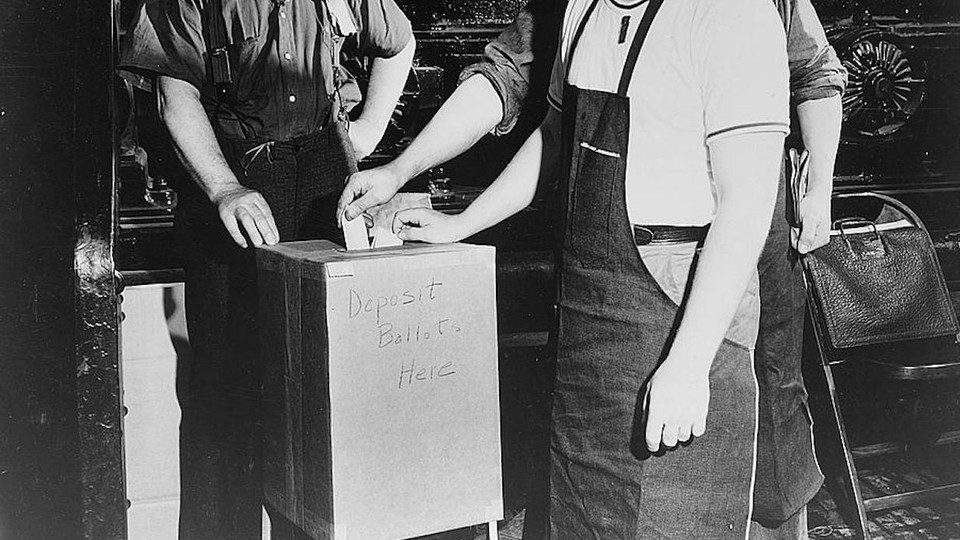

That movement, I believe, is essentially sound. The existing situation, in democratic countries, is on the face of it preposterous. On questions of domestic policy, in such countries, the people are constantly consulted. An insurance bill, a shop-hours bill, an education bill, a land bill, are canvassed eagerly and passionately in Parliament and the country. The whole press is set in motion; public meetings are held, deputations are arranged, ministries rise and fall. But where hundreds of millions of money and hundreds of thousands of lives are concerned; where the very existence of the country is at stake; where the decision to be taken involves not an extra tax, or a tentative experiment in social legislation, easily to be recalled or modified if it does not succeed, but the immediate summoning of the whole manhood of the country to kill and be killed in ways of unimaginable horror; when, in short, that very thing to the fostering and development of which every act of man, private and public, is rightly and exclusively directed; when life itself is to be destroyed wholesale, that decision, the most terrible any nation can be called upon to take, is precipitated by the fiat of half a dozen men, working in the dark, without discussion, without criticism, without a 'by your leave' or 'with your leave'; and those who are to sacrifice, in pursuance of it, everything which hitherto they have created and cherished, have no other choice than to accept the decision and pay the intolerable price. Surely only a god should have such power over men! And we, give it to an emperor or a secretary of state!

That, in brief, is the general case for democratic control of foreign affairs. And to any one who believes at all in the root principle of democracy, the control by men of their own lives and their own affairs, it must seem a strong one. There are, however, real difficulties felt in accepting it even among men otherwise democratically minded. And these difficulties must be fairly considered.

It seems to be thought by many that there is something about foreign policy peculiarly difficult to understand; that it is a thing of mysteries and special faculties, so that, although the methods of representative government may be trusted to conduct us safely through all the intricacies of our home affairs, though the people, roughly and in the last resort, are fit to decide about free trade and tariff reform, contributory or non-contributory insurance, the nearer or remoter effects of this or that method of taxation, and all the innumerable questions, difficult even to experts, that are raised by almost any of the legislative measures adopted year by year in progressive countries; yet the same people are specially and peculiarly unfit to judge about international relations.

This contention appears to me mistaken. Foreign questions I suggest, are commonly simpler and more comprehensible than domestic ones. The difficulties connected with the former are rather moral than intellectual. The hard thing is not to see what would be the right thing, but to get the right thing done, where, on every side, there is suspicion, fear, jealousy, and bad will.

Let me illustrate from some contemporary issues. Take the case of Morocco. Essentially, what was it? The French wanted to annex Morocco. The Germans were opposed to this, mainly because they were interested in the trade and resources of the country. The British were willing to consent to a French annexation, so long as the strip of coast opposite Gibraltar did not fall into the hands of the French or of any strong power. Nothing can be simpler than all this. It is not an intellectual problem at all. It is a contention for power and influence. Compare it, for difficulty of an intellectual kind, with the question of the ultimate effects on employment, wages, and prices, of a protective tariff. Yet it never occurs to any one to withdraw this latter question from the ultimate control of the people.

Take again the Balkan question. It is, of course, intricate. It requires for its solution knowledge of a number of facts about races, boundaries, and the like. But so far as questions of general policy are concerned, — questions that alone could be laid before a Parliament, — the matter is simplicity itself. Is Austria to eat up those peoples? Is Russia to eat them up? Or are they to eat up one another? Or is such an arrangement to be promoted as will separate out the nationalities, so far as may be practicable, and permit them each to develop freely in their own way? The difficulty here is to get people to do the right thing, not to see what the right thing is. And so far as the Balkan question concerns this country, I conceive Parliament to be as competent to decide what attitude we should adopt toward it as it is to decide upon the desirability of fixing by law the wage of agricultural laborers.

Or take the Mexican question. It is complicated of course. But the main difficulty for the ordinary citizen in forming an opinion about it is that he is kept ignorant of essential facts, such as the operations of the American and British oil or railroad interests, and their influence on the political situation. But if the facts were sufficiently made known, it seems clear that the decision of American policy would turn upon the answer to be given to certain questions which are exactly of the kind that ought to be submitted to the people, as: Ought we to recognize any government that can keep order in Mexico, or only such a government as stands for the interests of the Mexican people? Does American honor require us to go to war because the American flag has been insulted? Or because American citizens have been murdered on the frontier? Is the Mexican anarchy so serious and incurable that the United States have an interest and a duty to end it at the cost of a long and bloody war?

These are not easy questions to answer, even when the relevant facts are known. They will be answered differently by different temperaments. But they are not—like tariff questions, for example—questions for experts. There can be no experts in such matters. The problems are moral—for what issues will we take what risks and make what sacrifices? And it is exactly such questions that a democracy exists to answer.

It may be urged, in reply, that the objection to democratic control of foreign affairs is not that the questions are too complicated, but that they are too important for popular decision. Their importance is, I think, often misrepresented by those who concern themselves with international relations. They are apt to assume that the real business of a state is its foreign policy, and that domestic policy is a kind of sordid game, dividing a nation and weakening it in the pursuit of its true purposes. Whereas a just estimate would show that the contrary is the case: that, for example, the domestic questions that have been rightly preoccupying England and France during the last decade touch vitally those real needs of men and women which it is difficult to bring into any relation at all to the issues that led up to the war. Still, foreign policy is very important, if only because it may produce war. But then, what reason is there to suppose that, for this reason, the people, if properly informed, would be unfit to deal with it?

In fact, two opposite charges are brought against them, either of which might be true at one time or another. It is supposed that they would not be ready to face the test of war, when it was vital to the nation's interest that they should. And it is supposed that they would rush into war when their wise counselors would have kept them out of it.

Either of these things might certainly happen. But what happens now? What has been happening for centuries? Let us take the present war. What are all Englishmen, Frenchmen, Russians saying? Are they not accusing the German government of precipitating upon Europe a monstrous and unnecessary war? Are they not urging that the only way to prevent such a catastrophe in the future is the democratization of the German constitution? That is, precisely, the calling in of the people to put an end to aggressive jingoism! Perhaps that method might be unsuccessful. My point is, that the other method has also been unsuccessful. Or look at Austria. These diplomats who sent the ultimatum to Servia, who refused to extend the time-limit, who rejected recourse to arbitration, who rejected diplomatic mediation—could the parliament of a democratic country have done worse? Is it not practically certain that it would have done otherwise and better? Or turn to the case of Italy. The Italian government, we are told, was forced into the war by popular enthusiasm. I do not know whether this is a true account. But, if it be, for those who believe in the cause of the Allies it is an example of the sound instinct of the people, defeating the erroneous calculations of statesmen.

It is true that upon foreign policy issues of life and death hang more immediately and perilously than upon domestic. It is true that parliaments and peoples cannot be trusted to decide with infallibility right judgment. But that is true also of statesmen and diplomats. There is nothing special about foreign policy which makes democratic principles less applicable there than in other departments of national life. Broadly, almost every question of foreign policy is one of power, or of the prestige which is a guaranty of power. And it is precisely on these questions of power that the people ought to pronounce, since it is their blood that has to purchase or maintain the power. What bearing has this 'power' on the good life of men, our own or that of others for whom we may be rightly responsible? There is the most general problem of foreign policy, put as it ought to be put. How the people would answer it I do not take upon myself to say. I think they would answer it not as the diplomats have done. But, in any case, it is for them to answer it, if it is for them to answer anything at all. I doubt whether any one will deny this who at all accepts democracy.

There is then, I would urge, on the face of the facts, the same reason for subjecting to the public control the issues of foreign policy that there is for so subjecting any other issue. This does not imply the dispensing with training and knowledge. It implies the putting of that training and knowledge at the disposal of the nation for its instruction, and the acceptance of the verdict of the nation thus instructed. We, in England, require a Salisbury, a Lansdowne, a Grey. Americans require a Root or a Lansing. But in a democracy these men are required, not to direct a passive nation, but to take it into their confidence and then leave to it the decision. Now it is clear that, in Europe, at any rate, the people have no control over foreign policy, even in countries otherwise democratic. This war certainly was sprung upon the British nation. True, after it had been so sprung, the nation endorsed it. But it was in the years preceding that the control ought to have been exercised. How the control would have operated must be matter of conjecture. But it is clear that, from a democratic point of view, the nation ought to have known what policy was being pursued and what the risks were. It could then have decided whether it would pursue a policy that might land it at any moment in a European war (in which case, presumably, it would have made the requisite preparations), or whether it would alter the whole direction of its policy, by proceeding, for example, on the lines indicated by Sir Edward Grey in his often-quoted dispatch.1 Or if it should have become evident, in attempting that change, that Germany was bent upon war, it would have been all the better that the fact should be known and the requisite measures taken. The result of not taking the nation into the confidence of the government was about as bad as anything could be—a policy drifting into war without making any adequate preparations for war.

II.

That the peoples of Europe have, in fact, even in countries otherwise democratic, no control over foreign policy will hardly be disputed. But the question remains, how does this come about? In detail, the answer will be different in different countries, according to the details of constitutional machinery and parliamentary procedure. But one fundamental fact applies generally. The people in no country have cared to know or control. In England, and no doubt in other countries, it is plainly true that the advent of democracy has meant, so far, not more but less interest in foreign policy. The new classes admitted to the franchise have, naturally enough, concentrated their interest on the domestic legislation that bears directly on the conditions of their life. This legislation, more and more, has taken up the time and attention of Parliament. The front benches have profited by the situation to withdraw foreign policy from the arena of party controversy. And this withdrawal has meant that discussion has been discouraged, and that the foreign secretary has been able to evade all requests for information, with the full approval of the bulk of members in the House. It is thus that the almost incredible thing has occurred, that the whole of our foreign policy has received a new direction, that Great Britain has moved away from her old friend Germany, and toward her old enemies France and Russia, that she has abandoned the policy of isolation and adopted that of alliances, and that Englishmen have made themselves liable to be involved in a European war on a gigantic scale and to be converted, contrary to the whole tradition of our liberties, into a military and conscript nation, almost without notice being taken in the country of this tremendous transformation, carried out by the Foreign Secretary and a handful of officials at the Foreign Office, without ever becoming, even in a subordinate way, an issue at a general election.

Now, it would hardly be honest to put the blame for all this on the Foreign Secretary and the Foreign Office. They prefer, no doubt, to conduct foreign affairs, autocratically, and are skeptical of the new point of view that an instructed democracy might bright to bear upon them. But, after all, in the English system any matter can be made public and brought under control if the people are determined enough to do it. And in England it must be admitted that, if this has not been done, it is because the people have not cared to do it. A foreign secretary would have had to vie information, if it had been made clear that otherwise there would be a vote of censure. And improvements in the machinery of our parliamentary government, useful and necessary as they may be, will not ensure democratic control, unless the people are determined to have it. Will they be determined? I cannot say. But after the experience of this war, it does not seem likely that they will revert to the illusion that foreign policy does not concern them.

The popular control of foreign policy will become possible, then, in democratic states, if, and only if, the people care enough about it to insist upon having it. But not all states are democratic, or likely to become so in the immediate future. And it is urged that democratic diplomacy must be at a disadvantage when it has to deal with an autocracy. But this is not self-evident. Has autocratic diplomacy, in fact, shown itself to be so intelligent and effective? German diplomacy certainly has not. It has led Germany into a war in which she is faced by a coalition unexampled since that which combined against Napoleon; and no one is more critical of German diplomacy than the German people.

Autocracy is no guaranty of good diplomacy. Nor, of course, is democracy. There can be no such guaranty. The advantage of democracy is that it puts responsibility for failure where it should reside, with the people who have to take the consequences. And to those who urge that the people, in fact, would be less careful of the national interest, and less willing to make sacrifices for it than professional diplomats, it must be replied, first, that there is no evidence of this; secondly, that if it were true it would still be no argument.

The time has gone by for intrusting the destinies of nations to the supposed wisdom of experts. Experts, if indeed they exist, should advise, they should not control. The decision must rest with the nation, that is, with the total result of all the forces, material, moral and intellectual, progressive and regressive, pacifist and militarist, which combine in it and contend for mastery. To desire to withdraw foreign affairs from the control of this growing life, to keep them as a mystery for a profession, or a clique, or a class, is to attempt to fasten upon the present and the future the stamp of the past, to assume in this one department of life unchanging facts and principles, and a finished science. People who so think have too narrow a conception of democracy. Democracy is the whole sum of the arrangements whereby all the faculties of a nation are brought to bear upon its public life. The representative system—itself, no doubt, capable and requiring much improvement—is the machinery by which the decisions thus reached are translated into action.

Our present conduct of foreign affairs, even in otherwise democratic countries, is a survival from a different order, where a nation was regarded as mere passive stuff from which a few men, with credentials held to be divine, should shape what figure they might choose. That order, I believe, has passed with the conceptions on which it rested. A new order is struggling into life. And from the principles of that new order no department of life can claim to be exempt.

Supposing democratic control to be established, what would be its effect on peace and war? I am one of those who think it would make for peace. Not that I suppose the mass of men to be less pugnacious and bellicose than the class that has hitherto conducted foreign policy. This war has proved, if proof were needed, that an artisan is of much the same stuff as a nobleman; an obstinate when he is in a fight, as averse from reason and reflection, as determined to go on till he has won and never to inquire what can be gained or lost by winning. Once let a war be on the near horizon and the people will lose their heads just as much as anyone else. But it is in the process of getting the war on to the horizon that I should expect a change. The governing classes have been influenced in their foreign policy, partly by the abstract idea of power, partly by class interests. They have been appealed to by the pride of being a 'dominant race'; by a sporting feeling about war; by an instinct that war puts them back into the position of ascendancy to which they feel that they have a natural right.

These are the 'aristocratic' motives, plainly very strong in Germany, and not without considerable influence in England. To these must be added the more modern motive of plutocracy: the intrigues with governments of financiers and traders to push their particular interests; that whole competition between the capitalists of different nations which, directly or indirectly, has been the cause lying behind recent wars. These motives democratic control would set aside. It would insist upon putting the plain question that has hardly begun to influence governments in their conduct of foreign affairs, though it is the only relevant question: How does your policy bear upon the life of the people? A radical transformation was begun in the whole direction of domestic policy when the much-maligned utilitarians brought that question forward in a way in which it could no longer be evaded. But the question has never yet been put effectively, and so that it cannot be evaded, to the directors of foreign policy. Democratic control would mean that it would be put; and the consequences, I believe, would be all favorable to peace. And that, not because the people are, as individuals, all pacific, nor because they are idealists, but because their general interest and outlook is favorable to peace.2

To what extent what has here been said about European conditions is also applicable to America, American readers can best judge. To a foreigner it appears as though the conditions of popular control were present there more fully than in any other country. The president, it is true, has enormous powers; and although he cannot actually declare war, he can, of course, conduct negotiations in such a way that Congress has no choice save to declare it. On the other hand, the fact that he is an elected officer, and, in his first term, commonly seeks reëlection; the absence of a trained bureaucracy with a tradition, in the conduct of foreign affairs, indifferent to and contemptuous of the will and the judgment of the nation; and the apparent desire of the president to feel the support of public opinion, and for that reason to take it into his confidence—these conditions seem to offer good guarantees that the foreign policy of America, as it comes to be more and more important, may not be withdrawn into that night of secrecy in which the wars of Europe are engendered.

From this point of view, it may perhaps be suggested, Americans would do well to watch very carefully the growth of an expert diplomatic service. For there seems to be nothing in the nature of the case to prevent such a body, once it has been created, from dominating a president necessarily preoccupied with other concerns, as it can dominate foreign secretaries in European countries, and so, by an imperceptible process, substituting its irresponsible decisions for the judgment of the magistrate elected by the people, supported by public confidence, which he has invited and received. In no department of democratic government is it so urgent as in this to solve the problem of associating expert knowledge with government without allowing the experts to determine policy.

Granting that the people in the different states should have an effective will to control foreign affairs, the machinery of constitutional government will have to be adapted to this purpose. The method of doing this must be worked out in each case by those who are conversant with the constitutional theory and practice of the countries concerned. It is, however, important to insist that there must be international as well as national publicity. All nations must have an opportunity, in the case of an acute dispute, of knowing the position and claims of all other nations. This can be done only through a full inquiry by an international authority which shall publish to the world its findings and recommendations.

The creation of an authority for this purpose, and an agreement on the part of the nations to refer their disputes to it, is the essential feature of that American 'League to Enforce Peace,' with whose proposals the governments of the states of Europe are openly associating themselves, and the inauguration of which in the United States may prove to be a turning-point in international history.

There is no magic means of conjuring war. The passions, the cupidities, possibly even the convictions of nations may provoke it in the future, as they have done in the past. But at least it should be possible to secure that, if there is to be war, it should be the people themselves that choose it with their eyes open; and that, if a whole generation of young men is to be destroyed, at least they should see the catastrophe coming and be able to affirm with full knowledge that so it had to be and that to them no choice was given. 'Εν δέ φάει καì ολεσσσν.' 'Destroy us, if it must be so. But let it be in the light.'

- And I will say this: if the peace of Europe can be preserved, and the present crisis safely passed, my own endeavour will be to promote some arrangement to which Germany could be a party, by which she could be assured that no aggressive or hostile policy would be pursued against her or her allies by France, Russia and ourselves jointly or separately.' (British White Paper, no. 101.) ↩

- That is, to international peace. I am not here discussing the causes or possibility of civil war. – The Author. ↩

littleaughtfundis.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1916/08/democratic-control-of-foreign-policy/557357/

0 Response to "Foreigners Continued to Have Control After Independence Because They Brainlyt"

Post a Comment